Geographical Locations in Footnotes

Early in the cataloguing process I catalogued “Vaughan’s Voyages” and it inspired me to work with footnotes for my END project because of the abundance of geographical locations in its footnotes. I started thinking about why the author had chose to include footnotes, if the extreme frequency of geographical locations could tell me anything about the importance of footnotes in assigning genre, and the relationship between the reader and the explanation of referential and fictional locations. Because these geographical locations are in footnotes, I wondered if I could figure out if certain places required more explanation, or if the presence of a location in a footnote meant that the reader was unlikely to be familiar with it. I also wanted to see if I could compare the presence of geographical locations in footnotes with that in the titles of novels END has worked with, and whether the comparison could reveal anything about the number of footnotes with geographical locations or any such correlation. If a title has a geographical location, is it more likely to also have footnotes with geographical locations?

I will now outline my methods in collecting the data for this experimental project. My main source for gathering the data is the END Flickr and the photos that have been added to the Footnotes album. These photos are added as the END cataloguers find and upload photos with footnotes. The first novel in the album I looked at was “Giphantia” and worked my way back through the preceding novels towards the beginning of the album. I had no idea how many footnotes a given title would have or if there would be geographical locations in any of them, but I knew that if “Vaughan’s Voyages” did then there must be other novels where referential and imaginary places required footnote explanations. I created a spreadsheet and organized my data in columns: Title, Place, Flickr link, Tag, Notes, Year, and Franklin link (to the record of the title). I collected data from 23 novels, which is an arbitrary stopping point. Ideally for this project I would have looked through every photo in our footnotes album for all the novels that END has catalogued, and I hope to eventually expand this project. Of these 23 novels, 22 are from Penn and one is from Swarthmore. In the time allotted I looked through 657 photos of our footnotes, and of those 206 had at least one geographical location in a footnote. In these 206 photos I found 510 separate instances of geographical location. I was able to organize and sort my collected data into Excel spreadsheets to be used for analysis and visualization. To visualize my data I used RAW to show all the locations and their frequency values, I used findlatitudeandlongitude.com to collect the data needed to make maps on CartoDB, which I used to map the locations I tagged as city and country. All the spreadsheets I used for data analysis and organization can be found in the public Google Drive folder Footnotes.

During the project there were challenges that came up due to the amount of data I collected and its content. I struggled to decide how to sort and organized the data because there were so many unique locations and I needed to figure out how to make the data more easily analyzed. I also needed to figure out what to do with instances of geographical locations that are ancient, imaginary, fictional, and how or if to map them on a modern geographical representation of the world. For the ancient locations in my data I was able to map them as their modern counterparts, but for the majority of the fictional and imaginary places or ones I tagged as “unknown” I was unable to map the data. Some alternative mapping examples: I added the frequency value of “Cordova” to the frequency value for “Cordoba” because it was an older spelling for the Spanish city, I added the values for “The City of Jupiter” and “Diospolis” to the value for “Cairo” because these are ancient names for modern parts of Cairo, and I left out locations such as “Forrest’s Coffee-house” and “Wenlo” that are fictional. Cleaning my data in such a manner allowed me to better map the cities and countries represented in footnotes and use the maps for analysis. I had a large amount of data but I had to work with the automated mapping program and this left me with only a percentage of my data I could easily work with. The unmappable locations can be found in the spreadsheet titled “fictional and imaginary locations” in the public Google Drive folder Footnotes.

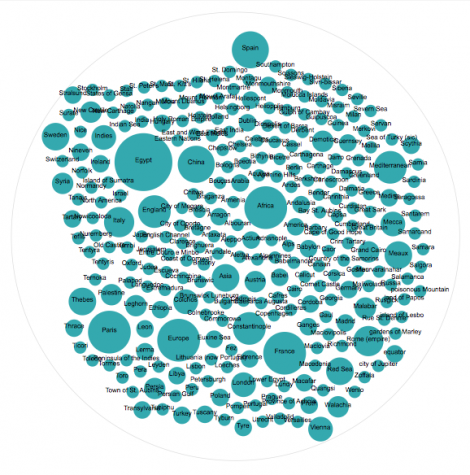

From the RAW visualization of all the frequency values for the locations I was able to clearly see which locations occurred most frequently in my dataset. These locations are Egypt, China, Africa, Spain, Paris, Europe, France, Mediterranean, and Constantinople, and clearly stand out on the bubble visualization. I learned from looking at this visualization which locations are mentioned the most and therefore were most important relevant to the understanding of the corpus of my dataset.

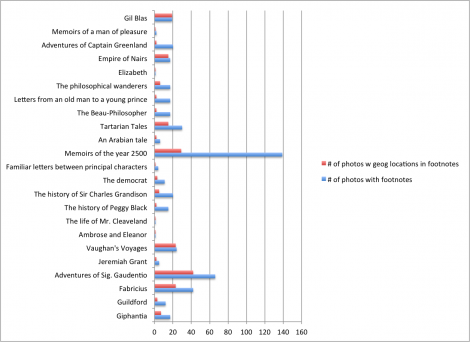

While this is a broad and mostly clear way of looking at the bulk of my data, delving deeper into the questions the footnotes raise requires a closer look and a different organization of the data. I made a chart for the novels I looked at comparing the number of photos on Flickr with footnotes with the number of those photos with geographical locations in the footnotes. The spreadsheet with this data can be found in the public Google Drive folder Footnotes and is labeled “# of photos vs # with location in footnote”. The image of the bar chart is labeled “photos with footnotes comparison.png” in the folder, and can be seen below:

Looking at individual footnotes in a few of these novels allowed me to start to think about whether the number of footnotes with geographical locations is an indicator of type of narrative. In order to answer this question and to think more about the purpose of the footnotes, I took a closer look at “Vaughan’s Voyages”, which has 24 photos with footnotes and 23 of which have locations in the footnotes, and compared it with the kinds of footnotes in “Adventures of Captain Greenland” and “The history of Sir Charles Grandison”, both of which have 20 photos with footnotes, a similar number to that of “Vaughan’s Voyages”. The footnotes in “Vaughan’s Voyages” seek to explain customs and provide referential information in order to enhance and illuminate the text. A quote from “Vaughan’s Voyages” is is as follows: “Tho’ perhaps I have not, in my past days, had any great regard for religion, and might leave it to be decided by chance, as the king of Macafar did:”(141) and is enhanced by the following footnote: “ Macafar is a large kingdom on the south part of the Celebes, an island in the Indian Sea. Near three centuries ago, they worshipp’d the sun and moon, as the most worthy objects of their adoration…”. This footnote gives more information about the place the author is writing about. “Vaughan’s Voyages” is a travel novel, so it appears as though there could be a connection between the genre of travel narrative and the presence of explanatory footnotes with geographical locations. Both “Adventures of Captain Greenland” and “The history of Sir Charles Grandison”, following this conjecture, do not fit into the travel narrative, seeing as out of 20 photos with footnotes, only 2 and 5, respectively, have geographical locations in the footnotes. The footnotes for “Adventures of Captain Greenland” seem to be more comical and less a serious addition to the information in the main text. An example of this is this quote: “…seasonable as well as unwholesome, for people, who have good healthful appetites to hold a fast at such a * biting time of the year.” (110), which has the footnote: “* Being about the middle of winter”. The footnote does not add interesting or explanatory information, but is instead entertaining yet unnecessary. Similarly, in “The history of Sir Charles Grandison’, there is no indication in the title that it is a travel narrative, and the kinds of footnotes it employs to explain parts of the text give information and the particulars of the characters and the content. For example, the heading for Letter VII on page 39 includes the following information “Miss Byron. In continuation. [On Sir Charles’s first letter from Bologna, Vol. IV. Letter XL. p. 277.]” which has the footnote: “* Several letters of Miss Byron, Lady G. Lady L. and Miss Jervois, which were written between the date of the preceding letter and the present, are omitted”. What is interesting about this quote is that there is a geographical location in the text itself, but one that does not require an explanatory footnote. According to the content of the footnote, what is happening concerning the letter and the people involved is what is interesting, and not the geographical location in which the letter is taking place.

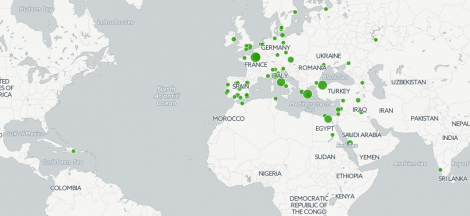

The last way I visualized and interpreted my data was through mapping visualizations. Using the tags “city” and “country”, among others I assigned to my raw data, I was able to map the frequencies of these two types of locations on a modern map of the world using CartoDB. The spreadsheet with all the instances of geographical locations and the tags I assigned to them (some but not all have explanatory notes in the spreadsheet) can be found in the Footnotes folder under the title “Geographical footnotes raw data”.

For the purpose of comparison, it should be noted that a similar project was done by a former END researcher, Emma Madarasz, who mapped the geographical locations in the titles of 18th century novels (link) to her project on our END With Known site). Her data shows that a significant number of places in the United Kingdom are mentioned in titles, something that contrasts with the locations in the footnotes of the novels I have chosen to work with. The titles she looked at also include countries such as Italy, France, and India, though not as many unique countries appear in titles as do in footnotes, as shown by my map visualization below. However, there are a significant amount of titles that include places in America or are connected with America, a place that is only represented three times in my raw data. Another difference between my project and Emma’s that I would consider for future work done with this project is that she included adjectives in her mapping of geographical locations. In the example of “America”, she included in her data the title “Amelia; or, the faithless Briton. An original American novel, founded upon recent facts.”, whereas I only recorded place names, and would have left such a title out of my data. For the future of my project I would consider collecting adjectives that related to geographical locations, and it would be interesting to see the effect of that decisions on the frequency values of places in my dataset.

The map visualization for “countries” I created is shown above. Using the locations tagged as “countries” allowed me to narrow the scope of my data and it was easy to map because almost all the countries in the footnotes I looked at were referential. The spreadsheet with the mapping information for the map seen above can be found in the Footnotes folder and is titled “countries mapping data”. The only location I had to alter was Turkey, which was spelled “Turky” in a footnote for “Adventures of Sig. Gaudentio”. The map shows that there are a significant number of footnotes that mention countries in Europe, especially Spain, France, and England, but that there are also a good number clustered around the Middle East and a few in North America, Asia, and Africa. Places in Europe would have been more accessible to people in England, and I would argue that these referential countries would have helped orient the reader to familiar places as well as foreign. The absence of places in South America and Australia shows that these places were either not well known to the authors or readers, or not relevant to the narrative of the novels I looked at for this project.

The mapping graph above shows the location and frequency of the locations I tagged as “city” in my raw data. Mapping these locations was more of a challenge because many were ancient cities or cities that no longer have the name used in the 18th century. An interesting example of this is that one of the cities mentioned in a footnote for “Vaughan’s Voyages” is Leghorn, which I found out was the English pronunciation for the Italian port city Livorno, and therefore I mapped Leghorn using the coordinates for Livorno, Italy. I had to do a lot more data cleaning for this visualization, and all my notes for this can be found in the Footnotes folder in the spreadsheet labeled “city mapping data”. From this map I can conclude that just like the “country” visualization, the nodes are mostly clustered in Europe and also around the Middle East. Therefore it was important for the authors to included clarifying notes about the cities in these regions, and that although many of these places could have been known or accessible to readers, it was still necessary to explain or embellish in a footnote. Maybe this gave readers additional information about places already within their grasp of knowledge or it simply added to the scope of their geographical understanding. It is also interesting that there is only one city mentioned in footnotes that is in the Americas, and that is Santo Domingo.

The thing that pops out from these maps is the centralization of this mappable data around Europe. One thought that comes to mind is that the types of locations I assumed would need explanation would be more faraway and exotic locations. These locations do exist in my raw data, but present the problem of not being easily mapped, and they do not fall into the more modern and restrictive categories of “city” and “country”. These two mostly Eurocentric maps put a spotlight on Europe and the nearby places in the world that would have be more accessible through travel, and moreover ones that are more conveniently referential.

This experimental project on geographical footnotes has been beneficial to me not only in the collection, cleaning, and piecing together of the data, but it has taught me the value of looking back on my methods in retrospect and realizing what things can be done to make this project better and more comprehensive in the future. This ranges from the simple task of making sure to record the number of footnotes of each novel and recording the novels I look at that do not have footnotes, to the larger conceptual choices of what novels to specifically look at and making educated decisions based on the topic of the project and the available information about the novels. The future of this project would no doubt include even more meticulous data collection and recording of notes. For example, in the future when an instance of a geographical location in a footnote is recorded, all the information about that place including tag, explanatory notes for the tag both from the footnote itself and the recorder, latitude, and longitude will be inputted into the raw data spreadsheet. I went back and did many of these things after all the instances had been recorded, and it would be infinitely beneficial to already have this detailed information for each instance at the end of data collection. I would also recommend that this project delve deeper into the content of the footnotes and the novel itself, and I am sure this would help me answer a lot of the research questions that this project has posed and that I have grappled with in attempting to determine the purpose of footnotes in these 18th century novels. Ideally this project for the future will include every instance of geographical location in every footnote of every novel END catalogues, and the possibilities for the interpretation and organization of this information are endless.