The Preface Project

Note: as of the summer of 2017, this project can also be viewed as an Omeka exhibit.

[Abstract] The Preface Project is a multi-modal digital archive exploring the relationships among truth claims, direct address of the reader, and authorial voice in the prefaces of 1760s novels. The archive conceives of prefaces as products of and catalysts for relationality, while weaving together new layers of enmeshment, through curated cataloging and audio, visual, and textual digital reproductions. Through the proliferation and linking of metadata, through the multimedia presentation of the prefaces, and through the open-access publication of the archived materials, the Preface Project generates new networks, entangling them with the conversations and relations of 1760s prefaces. While currently housed in a publicly-accessible Google Drive Folder, by the spring of 2016, the materials will transform into an Omeka exhibition.

Page viii-ix, preface of Mr. Cleveland.

There he first shewed me his father’s papers, which gave me so much pleasure and satisfaction, that I was very urgent with him to have them printed, persuaded that they would be, a very acceptable present to the public. The only objection he made to my proposal, was, the confused method in which they were writ, and the difficult task it would be to digest them… [Mr. Cleveland]

This quote is an excerpt from the preface which launched a thousand xml record searches. It comes from one of the first books I cataloged, The History of Mr. Cleveland. I expected a preface about the “natural born son of Oliver Cromwell” to be salacious and scandalmongering. Instead, it provides a staid and detailed backstory of the book: how the memoirs of Mr. Cleveland came to be edited, printed, and bound as a book for public sale. It elaborates on the staunchly virtuous character of Mr. Cleveland, who according to this preface, is nothing like the Merry King Charles II type of rake that I imagined. One should not, however, according to the preface, rely on imagined fancies. The preface claims authorship and historical existence for Mr. Cleveland. And it makes these truth claims through direct address of the reader: “…The histories of… private persons…serve as an excellent lesson to all who are desirous of avoiding those rocks on which others have split, and of meriting the highest character to which human nature can attain, that of wise men. That the following piece may justly be ranked among the latter, will, I believe, be readily granted by all judicious readers.” The reader! Seeing those words was like being called out of hiding; I was re-positioned from a pair of occulted eyes spying on an unaware text to a participant in a space-time crossing conversation. The preface acknowledges the reader’s role in the book, in the transmission of content; this acknowledgement signifies a mutual constitution of textual and extratextual worlds. This experience inspired a desire to learn more about how 18th century novels conceived of the reader. And so was planted the seed for my project, an archive probing the triangulation and construction of readership, truth claims, and authorial voice in the prefaces of 1760s novels.

First page, preface of Dialogues of the dead.

Lucian among the ancients, and among the moderns Fenelon, Arch-bishop of Cambray, and Monsieur Fontenelle, have written Dialogues of the Dead with applause. But in our language nothing of that kind has been published worthy of notice: for the very ingenious and learned dialogues written by Mr. Hurde are all supposed to have past between living persons. The plan I have followed takes in a much greater compass… [Dialogues of the dead]

The centerpiece of the project was the creation of digital copies of prefaces from 1760s novels, to address the fact that early novel repositories like Google Books, Hathi Trust, and ECCO, do not consistently include paratext in their digitization and OCR processes. I obtained my sample by searching the 520 and 500 fields of END’s catalog records, metadata without which I would not have been able to execute this project. The sample is based on the 1760s novels held in the British and American Fiction Collection of the University of Pennsylvania’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library; on novels draw from that collection and cataloged by END; and on novels whose prefatory invocations of the reader were caught by catalogers

To make the prefaces as accessible as possible, I photographed and transcribed them. This means that questions of emphasis (are certain words printed with capital letters or set off from the rest of the text, for instance) can be resolved by looking at the photographs, while issues of searching (for example, how a researcher is supposed to know which prefaces may be relevant to their line of study) can be resolved by doing a command F on the transcriptions. To the greatest extent possible, a balance has been struck between preservation of the preface-as-book object and the operationalization of the preface for research.

With the assistance of other END team members, I also created audio recordings of the prefatory texts. The audio recordings demand time and a deep listening—a close ‘reading’ of the prefaces, an attention to the prefaces as works of literature and not mere addenda. Hearing the texts read aloud highlights their invocatory nature: the strength of a narrative, authorial voice in the preface, and the importance of that voice’s interaction with the reader.

First page, preface of the Faithful Fugitives.

As curiosity is natural to the mind of man, and as every thing which tends to excite, without satisfying it, must prove, in some degree irksome, I have thought proper to give the reader some account how these memoirs fell into my hands. [Faithful fugitives]

Because utility for other scholars is one of my primary goals for the archive, I have kept the new, digitized representations of the preface I have created–images, audio files, and transcriptions–connected with the catalog metadata on the prefaces’ books. This ensures that future scholars can put the prefaces in their respective books contexts. The archives elevates the prefaces without divorcing them from the novels in which they were published in the eighteenth-century. Researchers can easily view information about the other paratext in the book (footnotes, table of contents), the narrative form of the main text, the people associated with the writing and publication of the book, and so on. Transparent metadata also allows a scholarly conversation to take place around my archive and the future exhibition. Without context for the paratext and clear paths back to my sources, it would not be difficult for me to make wild claims about prefaces. Without this metadata, no one could engage or critique my work, unless they sorted through the entire collection of British and American fiction at Penn by hand.

First page, the preface of the Hermit.

The preface. Truth and fiction have, of late, been so promiscuously blended together, in performances of this nature; that, in the present case, it seems absolutely necessary to distinguish the one from the other. If Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, and Colonel Jack, have had their admirers among the lower rank of readers; it is certain, that the morality in masquerade, which may be discovr’d in the travels of Lemuel Gulliver, has been an equal entertainment to the superior class of mankind. Now it may, without the least arrogance, be affirmed, that tho’ this surprising narrative be not so replete with vulgar stories as the former, or so interspersed with a satirical vein, as the last of the above-mentioned treatises; yet it is certainly of more use to the public, than either of them, because every incident, herein related, is real matter of fact. [Hermit]

“Promiscuously blended together” is an apt description for the relationship among fact, fiction, reader identity, authorial voice, and textual authority in the 1760s prefaces I have encountered. Prefaces are places for the provision of the context of a story (how it came to be written, why it is published with a frontispiece) and for the establishment of legitimacy (how a story will improve the reader’s morals, why moral improvement is utterly irrelevant in an entertaining tale, why its use of ‘pagan’ allegories is not heretical). This is somewhat obvious.

More illuminating is a focus on the fundamentally conversational nature of prefaces. They are not the print-version of a single voice piping context and the air of legitimacy into the willing ear of a generic reader. Rather, the prefaces are a melee of voices in negotiation. “Promiscuously blended together” aptly describes the relationships under contestation in the prefaces, relationships among fiction, fact, authorial authority, and the identity of the reader. A preface may envision and address multiple types of readership, may respond to the idea of the preface as an obligatory writing convention, may compare the novel of which it is a part to popular published works, may include quotes from Greek philosophers long dead, may claim to be historical fact and yet also claim that a factual text could be one that has fictional events , as long as those events could have conceivably taken place (even if they hadn’t in the particular manner and circumstances the novel imagined).

There is a palpable transactionality to the prefaces, one that reminds the contemporary cataloger that these novels were not always stored in air-controlled, dark rooms, but had lives embedded in the economic and cultural webs of the 18th century. The novels and prefaces, although set in print, were not static or insulated objects, but vehicles for and responses to human interaction.

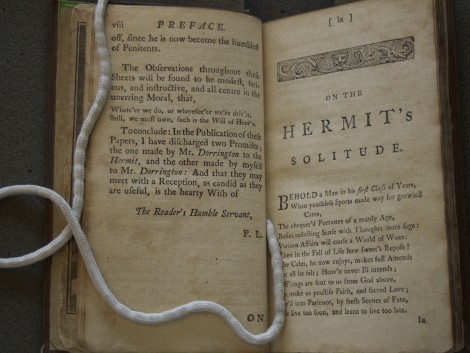

Last page, preface of the Hermit.

Whate’er we do, or wherefoe’er we’re driv’n–Still, we must own, such is the will of heav’n. [Hermit]

The Preface Project is still a work in progress. Eventually, the photographs, transcriptions, and audio records will be available, along with their corresponding novels’ END catalog records, as part of an Omeka exhibition. I am only now developing a full plan for the organization of the exhibition, the secondary sources on which it will draw, the data visualizations and analyzes it will contain, and the more granular themes it will address. For now, a folder containing preface transcriptions, audio recording, catalog records, and images is publicly available through END’s website. Documents further detailing my sampling and archiving methods are also be included in the folder.

Works Referenced

Genette, Gerard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by Jane E. Lewin. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Langford, Larry L. “Retelling Moll’s Story: the Editor’s Preface to ‘Moll Flanders.’” The Journal of Narrative Technique 22, no. 3 (1992): 164-179.

Ratner, Joshua Kopperman. “Introduction” to “American Paratexts: Experimentation and Anxiety in the Early United States.” University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons: Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2011.

Barchas. Janine. “Expanding the Literary Text: a Textual Studies Approach.” Graphic Design, Print Culture, and the Eighteenth-Century Novel. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 1-18.

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Image Music Text. Translated by Stephen Heath. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 142-148.