The Life and Opinions of Twitter Bots: 18th Century Prefatory Paratexts, the Capacities of Social Media, and Fact Checking

When I first started cataloging early novels, having no experience with 18th century materials and little historical knowledge of the 1780s social world of authors and readerships, I was struck by many of the differences between those books and their contemporary equivalents.

Looking at a random book in my backpack I had brought to read on my train commute to work - The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon - (which, admittedly, I still haven’t read), the paratextual data was completely different: Adventures opens with a page of praise for the novel from different publications (The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, &c.), and then includes a page devoted to a list of Chabon’s other works, an incredibly in-depth copyright page, an author’s note in the back in which Chabon thanks a large number of people by first and last name and lists a large number of books the author found helpful during his writing process, and finally an About the Author blurb. Were I interested in learning more, I could simply Google search any number of things, buy all of Chabon’s other works on Amazon (or else read them online), read Chabon’s tweets (or others’ tweets about him), click through related Wikipedia pages, watch interviews with him on YouTube, read full book reviews, so on and so forth. The data is, in many ways, freely accessible and richly linked.

For 18th century novels, on the other hand, the paratextual data is plentiful and deep, but profoundly different. Though they frequently include pages and pages of prefatory material, many works, for example, are anonymous, list a publisher only by their last name, or include a an introduction that refers to some nameless, and therefore largely unresearchable, Duchess, scholar, friend. In many cases, my carefully curated Google searches appear to return nothing related to the book I hold in my hands.

With this in mind, for my personal project I planned to analogize 18th century paratexts to modern day authorial social media presence. In the absence of the Internet, television, and radio, these paratexts (Prefaces, To the Readers, Introductions, Advertisements, Notes) are, in many cases, the sole source of immediately accessible information on the author and the book’s origin (both to an 18th century reader and to myself). Like social media presences, paratexts are means by which authors divulge information about themselves and their work, engaging with their readers as a fleshy human being (if one physical distant and on-the-page), as opposed to a disembodied fictional narrator.

To represent this comparison, I created a Twitter bot that tweets fragments of 18th century prefatory paratexts. Twitter is an online social media platform founded in 2006 that allows its users to share and read 140-character messages (“tweets”). Unlike social networking websites like Facebook, users do not have to mutually “friend” each other–one person can “follow” another person, and therefore see their tweets on their feed, without the other person following them back. This sort of platform allows for a unique variety of popular userships: “regular” individuals can have personal Twitter accounts, but so can, say, celebrities and bots. Most celebrities (musicians, actors, authors…) have a Twitter account where they can tweet about their daily life, participate in public conversations with other users, or market themselves by sharing information about upcoming appearances, tours, and work. Their fans can follow these accounts and keep up with their favorite celebrities, resulting in a largely unidirectional sort of conversation: celebrities tweet, their fans read, “like”, and “share” those tweets, without, in many cases, the celebrity ever doing the same in return. This is much like the case of readers and authors, both modern day and 18th century - readers learn about authors, not by having independent relationships with authors, but by consuming published material by or about the author, be that tweets or prefaces.

Twitter bots are accounts that, while programmed by human individuals, tweet on their own accord, drawing from databases, corpuses, or whatever else, at the hand of the bot’s programmer. Like celebrity accounts, much of their output is unidirectional: they amass many followers and readers without necessarily following anyone, using hashtags, retweeting, direct messaging, or what have you. Twitter, though it attempts to ban fake or spam accounts that detract from other users’ experience, does not suspend bot accounts for simply being bots. Because the kind of content bots can produce is so diverse, ranging from humorous to political to mundane, they can accrue large, voluntary readerships and contribute to the “social” world of Twitter. Notorious Twitter bots include @everyword, which began in 2007 to tweet every word in the English language one at a time; @congress-edits, which tweets every time a Wikipedia article is edited from an IP address associated with congress; and @thinkpiecebot, which generates and tweets fake thinkpiece article headlines.

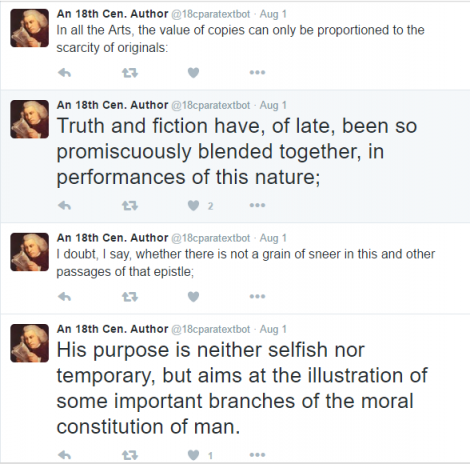

To build my bot, I used Zach Whalen’s Google spreadsheets-based program and instructions. I aggregated plaintext versions of paratexts from Project Gutenberg as well as from END researcher Kat Poje’s Preface Project. I then divided this corpus into shorter fragments by hand, formatted the fragments such that the file was CSV readable, and fed the file to my bot in order that it would tweet a random fragment (so long as it was 140 characters or less) every 2 hours.

After creating this bot, however, I found that it did not really demonstrate what I had intended it to compare (authorial self-representation). My bots’ tweets hardly approximated anything that a contemporary author might tweet, in style or content. While this doesn’t exclude both tweets and paratexts from being mediums of self-representation, creating a Twitter bot of 18th century paratexts doesn’t necessarily make this clear: tweets from contemporary human authors are more various and intentional in that they were formulated to be tweeted. They are the right character length; they make sense individually; they include links, videos, and .gifs. My bot’s fragments are often nonsensical, silly, incomplete–unlike complete Prefaces and unlike a human’s tweets, but very similar to the kind of content produced by Twitter’s most popular bots. My bot’s tweets feel very obviously bot generated, even though all of its content was, at one point, written by a human being. My bot’s tweets are fragments of material that originally preceded a novel’s text, and without that context, most of the tweets make little sense. This “failure,” however, transformed my project into an exercise in the capabilities of Twitter bots, and the complex world of fact and fictionality.

Many of the 18th century novels we cataloged this summer claim to be based on true stories. Occasionally, they are, but often they are fabricated, or else so closely mimic what might be a truth that neither an 18th century reader nor a modern one can parse fact from fiction. Many of my bot’s tweets contain bits and pieces of truth claims. Interestingly, more than my bot replicates the world of authorial self-representation, I think my bot operates as a unique commentary on the ambiguity of fiction and on 18th century knowledge production. Though my bot’s corpus draws on popular 18th century books whose plaintext versions can be easily accessed online, my bot’s corpus draws equally on prefaces transcribed from Kat Poje’s Preface Project, which focuses on more obscure, noncanonical books and which, as of right now, only provides access to pictures (and not a searchable text) of these materials. While I intend to eventually organize, upload, and make accessible the corpus I used, at the present moment my bot’s tweets are some of the only, if not the singular, online text transcriptions of these prefaces. Were someone interested in figuring out which book a particular tweet was originally sourced from, a Google search of the text might bring no results. While I assure that these tweets are from 18th century prefaces, what good is my assurance? How different is my assurance from an 18th century author’s prefatory truth claim? Though my bot makes use of the digital, its data is not linked in any way. The fragmented, decontextualized medium of a Twitter feed allows these texts to remain obscure, to reiterate their ambiguous truthfulness in the digital age in a way that, say, The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon could never have done.