18th-Century.txt: Early Novels and Digital Remediation

I. Background

My early inspiration for this project arose out of reading digital editions of classic novels online. Like many a college student, I sometimes seek out free ebooks of works in the public domain when I need to read a book for class but want to avoid paying for them. The quality of these online texts, however, often pushes me back to the bookstore. While websites like Project Gutenberg tout thousands of online texts freely available for use, the ebooks they host are cobbled together from a variety of previously published editions. Readers seeking simply to enjoy a classic text will also come away disappointed, as Gutenberg’s works are formatted so poorly and plainly that they may find even keeping their place is a slog.

Screenshot of an ECCO fulltext.

Scholarly electronic archives have higher standards of proofreading and increased search functionality compared to their free counterparts, but may still support interfaces that make their texts difficult to read. For instance, Eighteenth Century Collections Online hosts a vast corpus of full texts and scans of early novels online that would otherwise be unavailable, but has not updated its interface in years. If a scholar would actually like to read one of the novels it hosts, they would either have to settle for an ugly full text file, or struggle through microfilm scans for novels that lack electronic transcriptions. I began this project by asking myself if there was any way that I could produce a digital edition of a text that would be enjoyable to read.

II. Research and Project Conception

After doing research into digital texts, I decided to organize my project around two central cruxes. The first crux is what I call “Problems of Digital Archival,” a topic which digital humanities scholar Matthew Kirschenbaum has written extensively about. Although we often think of digital texts as “safer” than their paper counterparts because they lack a physical presence, cannot decay through exposure to the elements, and can be spread across multiple devices, digital texts are in fact quite fragile. Digital texts always require some sort of computer medium and interface so that people can interpret them, and these mediums are often not built to last. For instance, anyone can make an Aeon account to access books that are hundreds of years old in the UPenn Libraries’ collection, but it is almost impossible to access hypertext literature created exclusively for floppy disks today because the devices that use floppy disks have largely been discarded. Without a computer digital texts are just binary code, and most humans can’t read binary well.

The second crux the drove my project was understanding digital remediation. As Bonnie Mak writes, every digital text is a remediation of a paper text—it replicates the medium of the book in the medium of the computer. Thus we might say our use of pages in digital editions is somewhat arbitrary or even vestigial; computers grant us multiple ways to display a text, but we still construct and display them within the boundaries of the page or the scroll.

Ultimately I decided to address these two issues in my project by creating three digital editions of a unique early novel housed in the UPenn Libraries’ collection that was previously unavailable online. I settled on remediating The Royal Adventurers, or the Conflict of Love, a 1773 novel published in London which unfortunately turned out to be a lot less exciting than the title might have suggested.

III. Methodology

I conceptualized and produced each digital edition with a different intent in mind. Since digital texts that are more visually engaging use programs and coding languages that run a higher risk of future obsolesce, I chose to address either of my two cruxes in a single digital edition, but not both.

The first text I created was a plain .txt transcription of The Royal Adventurers intended for digital archival. I began by obtaining scans of The Royal Adventurers in END’s digital collection, which were produced at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries’ Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image (SCETI). I then downloaded these scans to a library computer running AABBY Finereader, a program that uses Optical Character Recognition technology to produce text transcriptions in .txt files from images. Unfortunately, the program has difficulties distinguishing certain letters in 18th century font styles (particularly the long “s”) and sometimes mistakes blank pages for text, so I spent a significant amount of time correcting the transcription by hand once I obtained it. This edition of the text is the most “scholarly” of the three, as it contains all the pagination and paratext of the original work. Although I chose to make this edition in .txt because it is a plain file format that will not become outdated anytime soon, the resulting text was no easier to read than digital transcriptions hosted by the likes of Project Gutenberg and ECCO. To increase the readability of the text, I also hosted the transcription in a format called markdown on a Github website. Markdown is both human and machine readable, so even if it becomes obsolete in the future there is a chance texts produced in the language can be salvaged.

Screenshot of the plain remediation hosted on Github.

I created the second and third digital editions in a program used to make interactive fiction called Twine. I selected Twine as my platform of choice because all texts created in the program are output as a static HTML file, which allows you to create complicated text with tens of different links and passages without long loading times. Since Twine texts are HTML based, you can easily change their appearance with a styling language called CSS. I intended the second digital remediation of the Royal Adventurers to be lightweight, minimalist, and readable. Using CSS I learned online, I created a digital text that replicates much of the structure of the original Royal Adventurers, with a few minor enhancements and changes to promote reader comfort. The text is entirely black sans-serif font on a white background, with the margins tweaked to resemble roughly the same dimensions as a page. The reader can access each individual chapter from a table of contents that appears towards the beginning of the text, and can decide to continue reading the novel or return to the table of contents at the end of every chapter. I wanted the reader to enjoy the text without an invasive amount of clicking, so I elected to eliminate individual pages in this edition and instead display each chapter as a single, scrollable page.

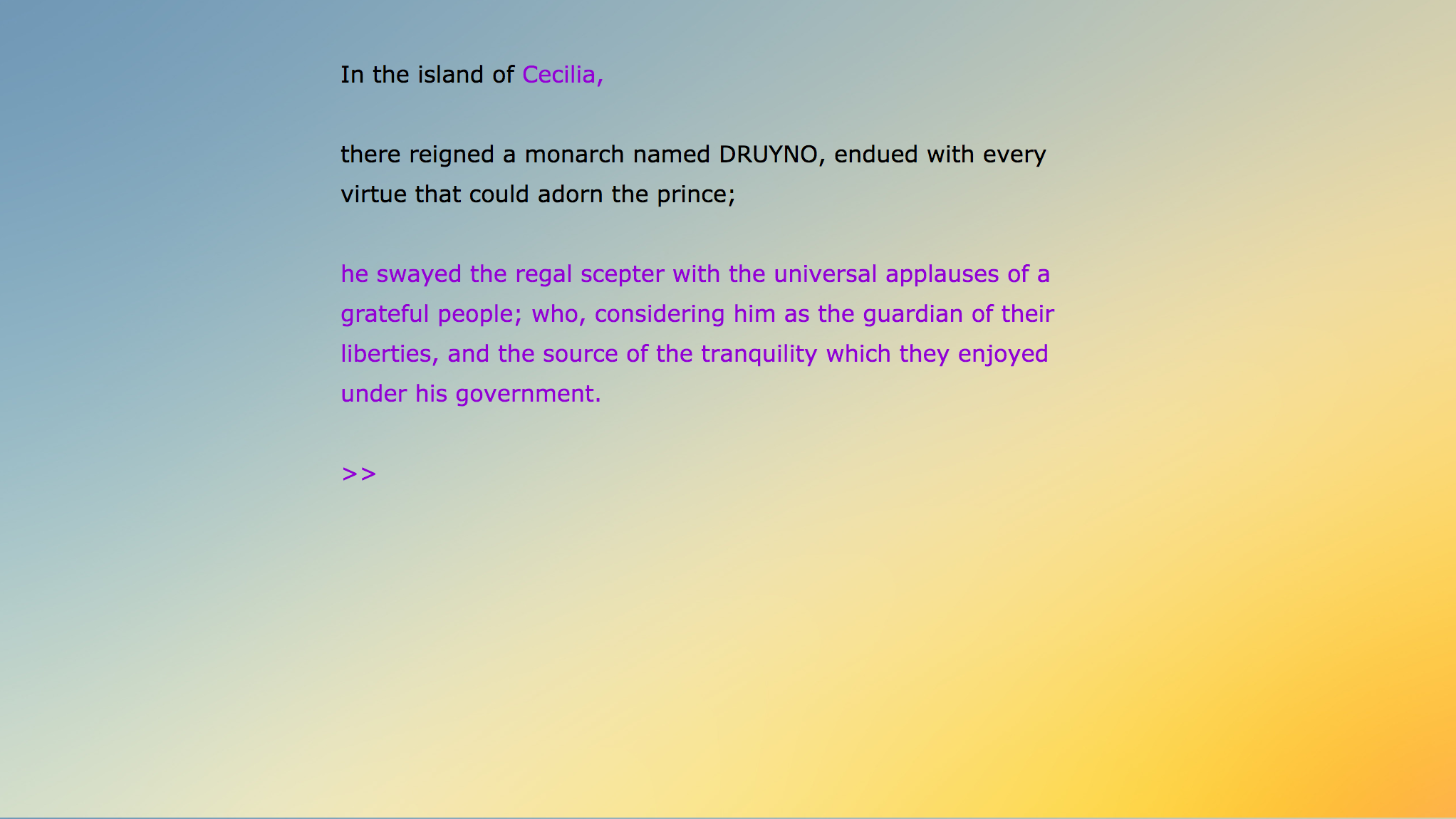

I would hesitate to call my final digital edition of The Royal Adventurers just a remediation—I changed certain areas of the text so much that it is probably more accurate to call it an adaptation. In this edition, I chose a four different chapters from the novel to experiment with allowing the reader to actually interact with the text, rather than just passively read it. This digital interaction is a substitute for the physical sensation of reading the novel in paper. My remediation of chapter I played with having the user control which parts of the text they can view; I turned various passages in the chapter into hyperlinks, and when the user clicks them additional text will either append to the current section or replace the linked passage.

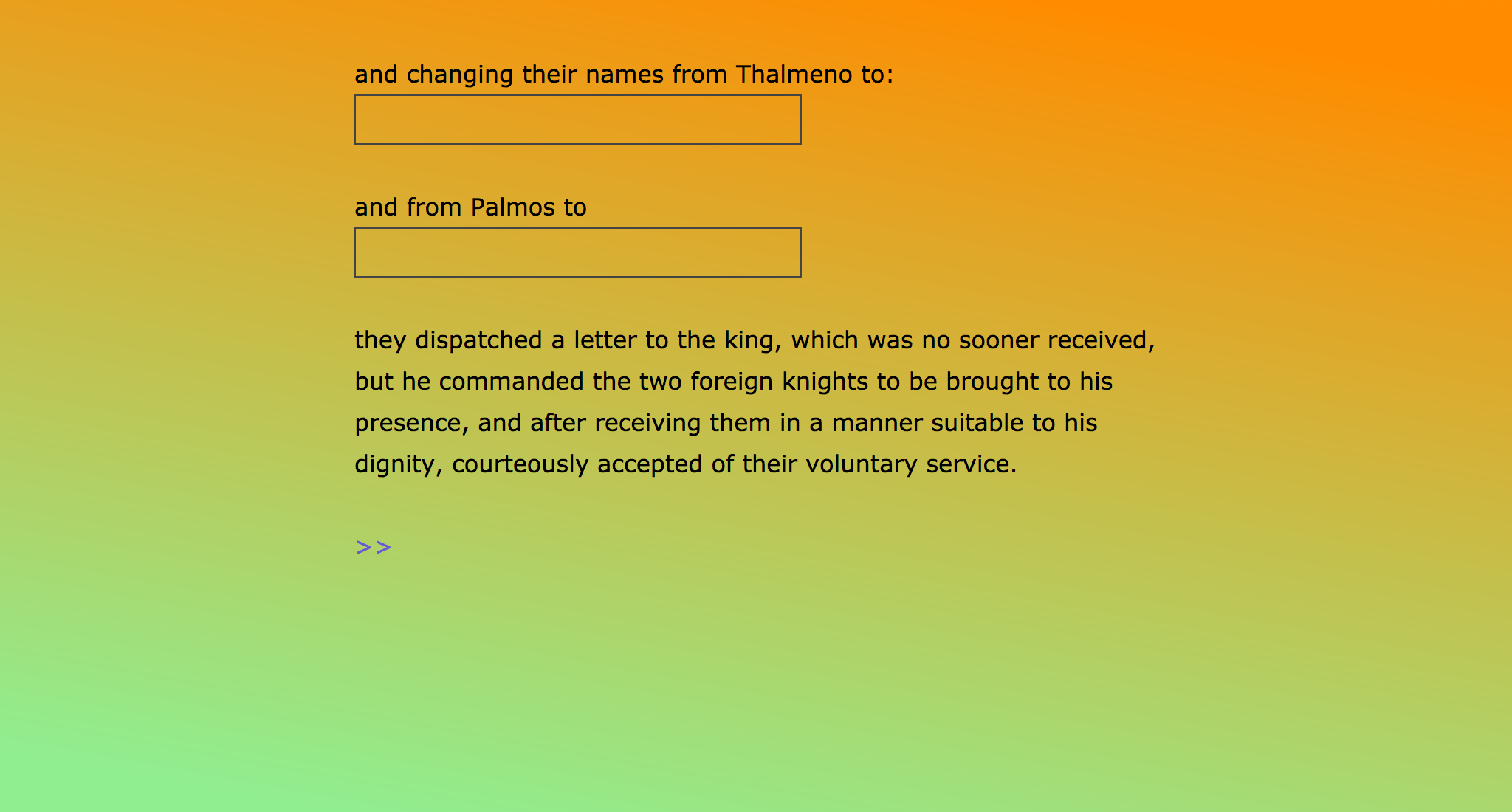

In chapter III I allowed the user to experience choice within the boundaries of an inherently linear story by providing them with dialogue branching options that nevertheless return to the original text through some sort of contrivance. In chapter V of the original novel, the titular adventurers create new names for themselves in a foreign country by rearranging letters in their names. In my experimental edition, I let the user create their new names, which persists through the remainder of the text wherever the adventurers use their aliases. Throughout this entire edition I also enhanced the aesthetics of the text through different backgrounds, font color, font size, and CSS animations (such as making certain words shake or disappear).

In this portion of the second Twine remediation, the reader creates an alias for both Royal Adventurers.

An example of how reader input affects portions of the second Twine remediation. Here the Royal Adventurers are referred to by the reader-created aliases “Kittenz” and “Mittenz.”

I tried to remain as faithful to the original text as possible even in this experimental remediation, but there are two discrete places in this edition that push it into the realm of adaptation. First, in chapter III I allow the reader to select a humorous (hopefully), fourth-wall breaking dialogue option that has one of the adventurers comment on the problematic aspects of their situation in the chapter. Second, I subvert the reader’s expectations of their choices not having any effect on the story through an alternate ending. If the reader chooses three “bad” choices in chapter III, the author of the text will chastise them for acting unvirtuous before the text gives them the option of returning to the title page. A reader who does not choose these options will not get this extra tongue-lashing, and will immediately receive the option of returning to the title page upon completion of the text. Even in this flagrant departure from the original text I tried to remain somewhat faithful by lifting some of “the author’s” words from the actual preface of The Royal Adventurers. The novel is an inherently self-reflexive medium—almost every early novel we catalogued this summer contained some sort of defense of itself in a preface or apology in its front matter. The two metafictional moments I added to the experimental remediation keeps the same sort of self-reflexive spirit in mind. Since the text affords the reader interactivity, it comments on the consequences of this interaction.

IV. Implications

The immediate implication of digital remediations, especially experimental adaptations like my third edition, is that they threaten the original meaning of the text. For instance, when I changed the background image to create a certain tone in my experimental text, my interpretation of the tone overrode the author’s original language. Each digital text contains two conflicting voices of various strengths. In the third edition especially my voice competes on almost equal terms with the author’s voice, whereas in the original edition the author’s voice exerts almost total authority.

We can extend this idea to END’s dataset at large. Each point of data in our database is effectively a remediation; a group of human catalogers decide what paratextual information is important in a particular early novel, and then convert that essential information into data. The book has now been remediated and shrunk into a point of data. Because every human who catalogues, however, is fallible, there is potential for errors or conflicting interpretations of what paratext and information is valuable in the dataset. This embodies one of the sticky aspects of the digital humanities, the blurred lines between qualitative and quantitative data.

View my Markdown reproduction of The Royal Adventurers

View my readable Twine remediation

View my experimental Twine remediation

Works Consulted

Kirschenbaum, Matthew and Werner Sarah. “Digital Scholarship and Digital Studies: The State of the Discipline.” Book History, Volume 17, 2014, pp. 406-458. Print.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew . “The .txtual Condition.: Digital Humanities, Born-Digital Archives, and the Future Literary.” Digital Humanities Quarterly, Volume 7.1, 2013. Web.

Mak, Bonnie. How the Page Matters. Toronto: U of Toronto Press, 2014. Print.