On Marginalia

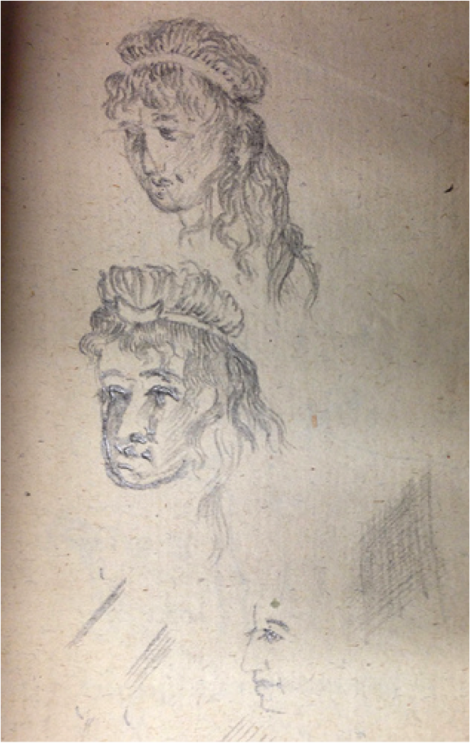

Image 1: Monimia

END currently deals with marginalia by placing it in its own 595 category. The field contains subfields for medium (ink, pencil, etc.), content, and extra notes. All in all, the field is extremely open, a necessity considering the range of information it is meant to contain. Marginalia by its very nature varies widely and pushes against any sort of uniformity. Leaving the field open appears to be an attempt to place all marginalia on an even playing field, ranking no type as inherently better. Everything from a detailed drawing [image 1] to a stray line or an “x” gets catalogued in the same way with only descriptive notes to truly distinguish them, making every marking seem to weigh about the same. The END field was designed to behave thus.

In practice however, marginalia cataloguing can be sporadic. As cataloguers we often tend to spend more time laboring over handwritten text (legible or otherwise), trying to accurately transcribe its meaning than looking at which sections have been underlined or marked in some other way and trying to decipher a meaning from that. Depending on the amount of detail in them, doodles can get more than a cursory description, but written words are still regarded as the most sought after marginalia.1 There is an understood, though debated, hierarchy of these accompaniments to the book that centers around our accepted and internalized definition of what marginalia actually is. This definition is text-focused not book-focused. According to the OED, marginalia are “[notes], commentary, and similar material written or printed in the margin of a book or manuscript. Also (in extended use): notes, comments, etc., which are incidental or additional to the main topic.”2 There is an underlying implication that marginalia should be related to the text/content of the book instead of the book-object, that although they do not have to apply, the notes and commentary should be relevant in some way. Not every coherent marking in a book fits into this definition, and consequently library marginalia gets left behind.

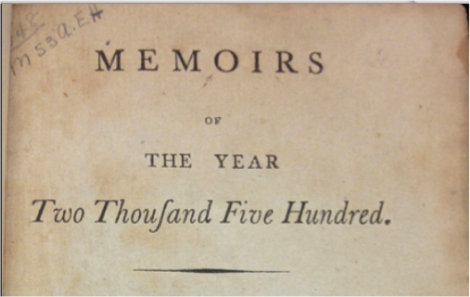

Image 2

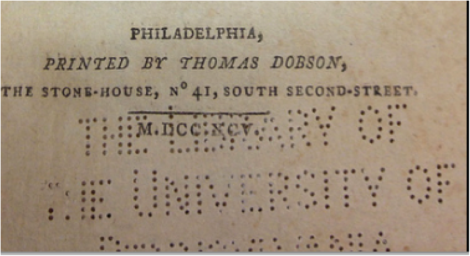

Image 3

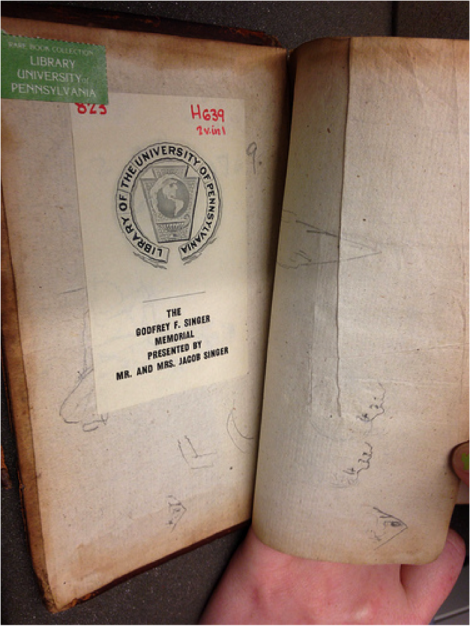

Library marginalia generally consists of sequences of numbers and letters written in pencil in the corners and on the edges of title pages and end paper [image 2]. These sequences are book as an object fits into the grand organizational structure of the library, where it fits in with the classification system of the institution (which in the case of Penn Rare Books and Manuscripts library can be Library of Congress, Dewey Decimal, or an institutionally specific system called Culture Classification). Occasionally they include stamps that press words (such as the name of a library) into the pages or that punch holes in the paper to the same effect [image 3]. By and large, END cataloguers choose not to include library markings in their 595 fields. If library marginalia is included in a record at all, it is usually captured as a 500 note, a catch-all field for information with no clearly defined home subject to the whims and judgment of individual cataloguers. Although not really marginalia by any definition, University of Pennsylvania bookplates [image 4] also tend to be omitted from records as an extension of the logic that finds the cataloguing of library marginalia unnecessary and redundant. The library marking and bookplates that do tend to be captures are those belonging to institutions other than the University of Pennsylvania, aka things that prove that the book had a life and a position in a collection before finding its way to UPenn. Marginalia that appears to be more recent and consistent with Penn’s system of classifying and marking up books is usually glossed over or ignored, the logic being that that information is captured elsewhere in the record.

Image 4

I would argue that although the information exists elsewhere in the record and functions differently than what we typically classify as marginalia, the fact of it having been written in the book is still important. It does not do to be only partly concerned with the object-hood of books. I also think that upon further reflection this institutional marginalia does not behave so differently from personal marginalia. Marginalia creates evidence of a book’s past life and of its interactions with people. It serves to both make the book a unique object, something that exists separate from the text printed on the page and is unique despite being a mass-produced commodity, and connect it to the world at large through references to or depictions of it. Library marginalia does this same inward/outward dance. It gives the book a singular identity through letters and numbers, differentiating it from all other copies that may be floating around in the world, yet it very clearly situates the book in a larger system. The library system may not be able to compare with the entirety of the world, but it is still something significantly larger than the book itself tethered to the book through writing. Library markings prove that a book has a specifically defined place for itself, a niche carved out in a shelf waiting for its return, and that it fits into a larger body of knowledge.

Basically, all I am saying is that library marginalia is a part of the book as an object. It is part of its physical being and its history. By choosing to exclude it we choose to ignore arguably one of the most important factor in its continued existence and the means by which we are allowed to access the materials. It may not be useful or time effective to capture it in the long run, but we should at the very least reflect on why we are doing so and what that means instead of dismissing it out of hand.

1 Considering how the majority of the cataloguers are English literature majors this should probably not come as a surprise. ↩

2 The oldest example for the use of the word “marginalia” included in the OED is from 1819, placing the introduction of the word into (relatively) common usage and the accompanying concept somewhere squarely in the middle of our time range (1660-1830). I am not saying that the concept of marginalia is unique to novels and related to their raise necessarily, only that both seem to gain traction and legitimacy around the same time. ↩